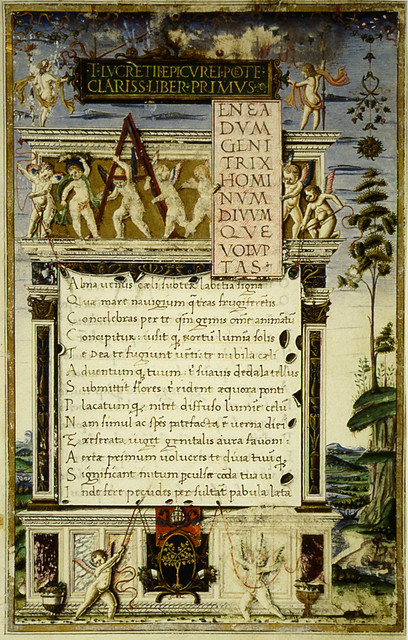

There is a priceless work of ancient literature that rests, now safely copied beyond risk of annihilation, within the world’s digital book databases, web servers, bookstores, and libraries. A few manuscripts from the middle ages survive, along with copies made painstakingly by hand, then printed widely once Gutenberg’s invention came into use.

On the Nature of Things is a poem of 7,400 lines written two thousand years ago by a freethinking Roman named Lucretius. It “yokes together moments of intense lyrical beauty, philosophical meditations on religion, pleasure, and death, and complex theories of the physical world, the evolution of human societies, the perils and joys of sex, and the nature of disease.” 1 It’s a wonder that it survived the dark ages, escaping the fiery fate of so many other manuscripts that did not conform to the iron-fisted piety of the almighty medieval Church.

And conform it certainly did not. Throughout his remarkable poem, Lucretius denies any divine influence or even interest in the affairs of humans. The universe was not made by the gods, and does not need their help to run its random course. We are all fortunate arrangements of atoms formed into living beings who exist only briefly, and just this once. We have no souls that outlast our bodies, so our pursuit is the happiness and pleasure that these brief lives of ours can offer. When the end comes, it is final, and we must accept it graciously.

Lucretius was very much a materialist. A person “can call the earth ‘Mother of the Gods,’” he allowed, “on this condition— / that he refuses to pollute his mind / With the foul poison of religion.” 2 He did not deny the existence of the old gods, just their influence on our world or any interest in it. “By their very nature,” they sat aloof, enjoying “perfect peace” and “immortal life,”

Far separate, far removed from our affairs.

For free from every sorrow, every danger,

Strong in their own powers, needing naught from us,

They are not won by gifts nor touched by anger.3

Whether out of poetic license, some lingering respect for the old traditions, or as a way of easing the pious into his starkly materialist worldview, Lucretius begins his monumental celebration of humanism by addressing one of those gods whose superstitious worship he disdains.4 The “Invocation to Venus” is a beautiful and erotic paean to the goddess of love, a celebration of how the “universe, in its ceaseless process of generation and destruction and regeneration, is inherently sexual.” 5

Now, for a few minutes, try to forget that you are an occupant of a frantic, attention-limited society twenty centuries after Lucretius scratched out his lines with quill pen on papyrus or parchment. You are browsing a blog with bills to pay and laundry to fold, and that sort of fast reading does not lend itself to the appreciation of thoughts formed in a more deliberate age.

But please do try. Savor the lines below, which have been so artfully translated—from manuscript copies several times removed from the long-lost originals—by an Englishman, John Dryden, three centuries ago. The words are stunning in their glorious sensuality and power, and are a bit daring for stiff-necked readers even today.

And enjoy the pictures interspersed, too. They are samples of my own long-running visual paean to nature, expressing the same ancient appreciation with modern tools.

Delight of humankind, and gods above,

Parent of Rome, propitious Queen of Love!

Whose vital power, Air, Earth, and Sea supplies,

And breeds what e’er is born

beneath the rolling Skies;

For every kind, by thy prolific might,

Springs, and beholds the regions of the light.

Thee, Goddess, thee the clouds and tempests fear,

And at thy pleasing presence disappear;

For thee the Land in fragrant Flowers is drest;

For thee the Ocean smiles,

and smooths her wavy breast,

And Heav’n itself with more serene

and purer light is blest.

For, when the rising Spring adorns the Mead,

And a new Scene of Nature stands displayed,

When teeming Buds, and cheerful greens appear,

And Western gales unlock the lazy year;

The joyous Birds thy welcome first express,

Whose native Songs thy genial fire confess;

Then savage beasts bound o’er their slighted food,

Struck with thy darts, and tempt the raging flood.

All nature is thy Gift; Earth, Air, and Sea;

Of all that breathes, the various progeny,

Stung with delight, is goaded on by thee.

O‘er barren Mountains, o’er the flowery Plain,

The leafy forest, and the liquid main,

Extends thy uncontrolled and boundless reign;

Through all the living Regions dost thou move,

And scatterest, where thou goest,

the kindly seeds of Love.

To thee Mankind their soft repose must owe,

For thou alone that blessing canst bestow;

Because the brutal business of the War

Is managed by thy dreadful Servant’s care; 6

Who oft retires from fighting fields, to prove

The pleasing pains of thy eternal Love;

And panting on thy breast supinely lies,

While with thy heavenly form

he feeds his famished eyes;

Sucks in with open lips thy balmy breath,

By turns restored to life,

and plunged in pleasing death.

There while thy curling limbs about him move,

Involved and fettered in the links of Love,

When wishing all, he nothing can deny,

Thy Charms in that auspicious moment try;

With winning eloquence our peace implore,

And quiet to the weary World restore.

Notes

-

Stephen Greenblatt, The Swerve: How the World Became Modern. W. W. Norton & Company (2011), Ch. 8. ↩

-

Book II, 658-660. Ronald Melville, trans. On the Nature of the Universe, Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford University Press (1997). ↩

-

Book I, lines 646-51. Melville trans. ↩

-

For a more nuanced view, see George Depue Hadzsits, “The Lucretian Invocation of Venus.” Classical Philology, Vol. 2, No. 2 (Apr., 1907), pp. 187-192. Available for free online courtesy of the University of Chicago Press. According to Hadzsits, the “Lucretian invocation of Venus, as a typical Epicurean prayer, must be interpreted in the light of Epicurean theory and practice—a prayer, then, with a deep, complex, religious significance to the sincere Epicurean himself, a prayer that included an emotional attachment to older traditions, to established customs and beliefs, and also an enlightened intellectual, Epicurean interpretation of such religious material.” He finds it “utterly unthinkable that in the Venus invocation Lucretius has been untrue to himself,” with a mere “conventional literary ornament” as a hypocritical pious preamble to his “literary monument to fearless honesty.” ↩

-

Greenblatt, p. 45. ↩

-

The servant was Mars. Melville provides this footnote to the line in his translation: “Venus restraining the warlike impulse of her husband Mars was a frequent subject of ancient as of modern painting (see especially Botticelli’s Venus and Mars). Their union was sometimes allegorized as bringing about harmony: they also look back to the two cosmic principles of ‘Love’ and ‘Strife’ of the fifth-century BC Greek poet Empedocles, who was one of Lucretius’ major models.” ↩